Myth-interpretation

Digging through literary mud

Disclaimer: The following article is a thought experiment. I have not read the entire Bible, I do not speak Ancient Greek or Ancient Hebrew, and I am not a biblical expert of any sort.

Here are three questions that get to the heart of something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately.

Is the Bible hard to understand?

Should the Bible be hard to understand?

Was the Bible hard to understand by intelligent, literate people during or shortly after the time it was written?

Answering these three questions in order gets progressively more difficult, but there’s a fourth question that needs to be answered before I attempt to answer the first three.

Who fucking cares?

For starters, I care! But that’s not how you answer a “who cares” question. “Who cares” is actually better phrased as “what difference does it make,” or “why does it matter?”

It matters because the Bible matters - whether you like it or not. The Bible is itself a library of many different books (the exact number of which is debated by christians and theologists) that, along with many other ancient texts, has shaped countless cultures and civilizations for thousands of years. Understanding the Bible is important in exactly the same way that understanding history is important, considering the Bible has its fingerprints all over human history for the past 3,800 years, give or take. Not to mention it is, to some, the literal word of god.

If that is an unsatisfactory answer to you, stop reading this article.

Is the Bible hard to understand?

In a word, yes. To the modern reader the Bible is difficult to understand for several reasons.

The people and places are unfamiliar to us, having been separated by thousands of years and thousands of miles.

The events that unfold, and the behaviors of the people in the Bible are foreign and strange to us when viewed through a modern, western, liberalized, materialistic framework.

The versions of the Bible we read are translations of translations (and often mistranslations, both deliberate and accidental), which diminishes the authenticity, nuance and context that was embedded in the original texts.

The Bible was written over many centuries by many authors who did not collectively conspire to ensure continuity, consistency and cohesion.

The style, tone and voice of the texts change from strict factual accounting to freely expressive poetry, making it difficult to know when to read it literally, and when to read it metaphorically.

I could go on, but you get the point. The Bible is not a book you pick up, read straight through, and walk away feeling as though you totally get it.

Should the Bible be difficult to understand?

What I mean by this is: "Is it necessary for the Bible to be difficult to understand?"

In my opinion, no it is not necessary. Writer’s strive for clarity. Obscure, clumsy and obtuse literature is the bane of every writer’s existence. Whether that’s because the Bible is the direct word of god - and god does not intend to confuse or deceive - or whether that is because the authors of the Bible were deliberately trying to record history as accurately and clearly as possible, it seems to me that the Bible should actually be easy to understand in the same way that a journalist would intend for their stories to be easy to understand, even if the subject matter is hard to believe.

So we have a text that is historically, culturally and spiritually significant, that is difficult to understand, even though it shouldn’t be. How do we square this circle?

That leads me to the final question.

Was the Bible hard to understand by intelligent, literate people during or shortly after the time it was written?

The honest answer to this question is “I don’t know.” Perhaps, “I cannot know,” since we cannot travel back in time to poll them. What we can do is become archaeolinguists. That is, we can strive to peel back the layers of history, trace back all of the (mis)translations, and otherwise attempt to think like someone who would have been among the first to read this ancient text.

Easier said than done!

It takes a substantial amount of work to place yourself into a culture that is 30 centuries old, but it’s not impossible. Lucky for you, I’m not going to attempt to do that here. Instead, I am going to provide an example of what it looks like when we reread a famous story of the Bible before and after we place ourselves in the time, place and culture in which it was written.

The Sermon on The Mount

Take for example Matthew 5:38–42 (NIV translation):

38 “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth.’

39 But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also.

40 And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well.

41 If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles.

42 Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you."

If you’re like me, this parable was taught to us as a lesson in pacification, non-violence and acceptance. But was this what Jesus was saying?

What might an archaeolinguist do to better understand this excerpt? Perhaps she would ask the following questions: who is speaking, who is the audience, and what is the context? The answers are 1. Jesus is speaking 2. to the Jews 3. about the Roman occupation of the Jews. A little more context is necessary to shed light on what is really being said here.

At the time, if a Roman soldier quarreled with another Roman soldier, he would strike the other soldier with his right hand across the Roman soldier’s left cheek in a typical punching motion. Contrarily, if a Roman soldier quarreled with a Jew, who was considered by the Romans to be lowly and undignified at the time, he would instead use the back of his right hand to strike the Jew on his right cheek, literally adding insult to injury.

Thus, by instructing them to “turn the other cheek” Jesus was actually encouraging resistance and action, not acceptance and pacifism. In other words, he was reminding the Jews that they are no better and no worse than the Romans, and that they are as deserving as any other when it comes to punishment or reward. He was reminding them of their humanity and their equal value.

And what about verse 41, “If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles.”

Similarly, at the time, Roman soldiers could force any Jew to carry their pack for one mile and no more, totally against their will. By telling the Jews to carry the pack of the Roman soldier for an additional mile, Jesus was not encouraging them simply to be compliant, peaceful and helpful, but rather he was showing them how even in this unjust world they could reclaim their dignity, sovereignty and independence by going one step further, despite the fact that the Roman soldier was not legally allowed to make such a request.

Well what do ya know? The exact same story, when read as though we are from the time and place from which the story was written, produces a completely different message! And more importantly, armed with the right information, it is actually easier to understand.

Think about it. Before this new understanding, we were told that the right thing to do when someone hits you is to let them hit you again. Why? Because pacifism is always right. Why? Presumably because violence is always wrong. Why? That part is still hotly debated by philosophers. We are left scratching our heads, accepting this lesson like swallowing a foul medication, uncertain of the effects it will take on us, but promised that it is good for our health.

Alternately, after we understand the speaker, the audience and a bit of context, not only do we more clearly understand what is being told, but it actually makes intuitive sense to us. Jesus is telling us not to tolerate discrimination, not to tolerate inequality, and to reclaim our dignity, our courage and our spine. This is a much better message!

So I’ll ask once more…

Was the Bible hard to understand by intelligent, literate people during or shortly after the time it was written?

Assuming the intelligent, literate people of the time inherently understood the culture from which they came, I would say the answer is quite clearly “No.” In other words, I imagine the Jews dispersing from the crowd after the Sermon on the Mount fully comprehending what was spoken, and I imagine the readers of this story either identifying with the Jews, or with the Romans, depending on their allegiances, but in neither case were they scratching their heads wondering “what is he talking about?”

These little nuggets of wisdom, knowledge and prescription are all over the Bible, as far as I can tell, but they have to be unearthed. They are not laid bare for us anymore because thick layers of history, culture, and translation separate us from the source. I don’t know about you, but it makes me feel better knowing that we weren’t so different from our ancient ancestors, and that they dealt with so many similar problems, and devised such similar solutions that we use and reuse thousands of years later.

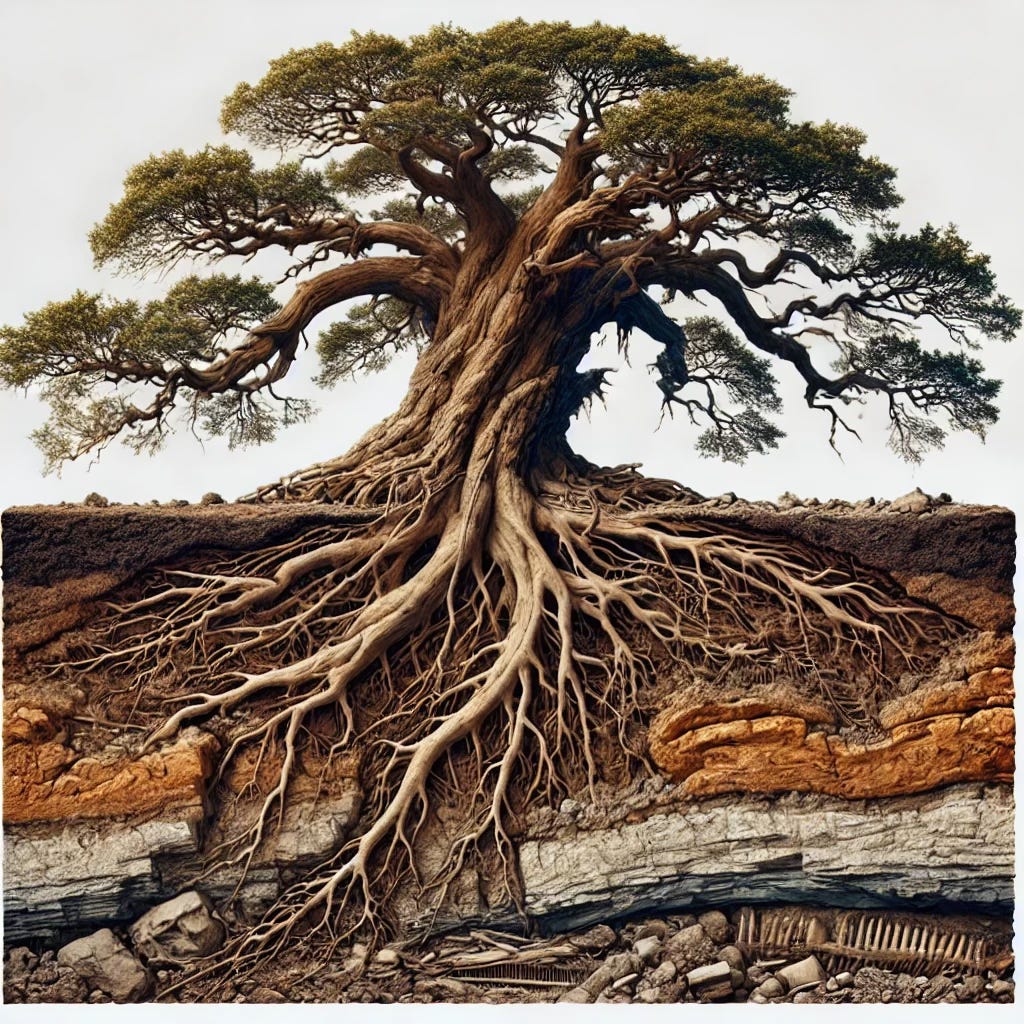

As I thought of this, an image popped into my head. Images always help me crystalize my thoughts so that I can remember them later.

The image is a cross-section of earth. At the top, on the surface, there is a tree with long, twisting branches, and deep, thick roots. At the bottom is bedrock, covered by layers of dirt, and bones.

The tree represents a modern work of literature like Shakespeare. (I’m being real fast and loose with the word “modern” I know, but stay with me.) The bedrock represents ancient texts like the Old Testament.

A modern reader in the time of Shakespeare probably would have struggled to understand any of his sonnets and plays at first pass. The same reader would likely also have struggled to understand the text in the Old Testament, but not for the same reasons.

The reader would struggle to understand Shakespeare because the language Shakespeare uses is novel, complex, dense and otherwise deliberately challenging. He invented words by combining stems from different languages (branches spreading far and wide). He relied on form and structure to frame his narratives (the trunk of the tree). He referenced characters and myth from ancient history, and relied on literary devices like symbolism and entendre to add layers of meaning to his words (deep roots). In order to understand Shakespeare, you had to trace the branches to make connections, and follow the roots to find the source.

The Old Testament, however, was written with an extreme economy of word. That is, in most cases, there were no references to ancient characters or places, there was no reliance on heavy description and allusion. The stories were told in a simple, straightforward manner, intended to be easily understood.

But as I said before, the same Shakespeare reader would not have this experience. The stories would not make sense to him, not because they are packed with complicated meaning, but because the simple message they intend to convey is caked and covered by centuries of literary mud.

Once the reader-become-archaeolinguist does her research, what once was complex, confusing and counterintuitive becomes simple, clear and obvious. In the case of Shakespeare, this requires reading classics, learning languages and understanding literary devices. In the case of ancient texts, this requires understanding the language and culture of the people when it was written, as well as the speaker and the audience. It’s hard work, that’s for sure, but it pays off in many ways, the most important of which, for me, is that we understand ourselves as products of our own culture, we understand our thoughts as a product of our own language, and we can more easily recognize patterns across time, which makes our ancient ancestors more like saints, and less like savages.

This is your best piece to date. At least for me. Specifically it addresses what most readers and followers of the Bible ask ourselves at least privately. Is this the divine hand of God writing the accountings? Or inspired followers telling end retelling until finally being put into written form and then discovered hundreds of years later and eventually passing some sort of test that a specific set of writing could then be considered a book in the Bible. Then comes the translations or mistranslations as the case may be. I find it both a miracle this book came into being and a miracle it was all written with a single God and a single son of God. No deviation from that. Which means many, many over long periods of time took the time and energy to write it down. What will we contribute? Texts? Old devices with who knows what still in tact?

I digress, this is good and interesting.